The five stages of grief, also known as the Kübler-Ross model, outline the emotional journey people often go through when experiencing loss—especially the death of a loved one. But grief isn’t exclusive to death. Loss is loss. Whether it’s the end of a friendship, a relationship, or the loss of a sense of self—grief finds a way in.

Denial. Anger. Bargaining. Depression. Acceptance.

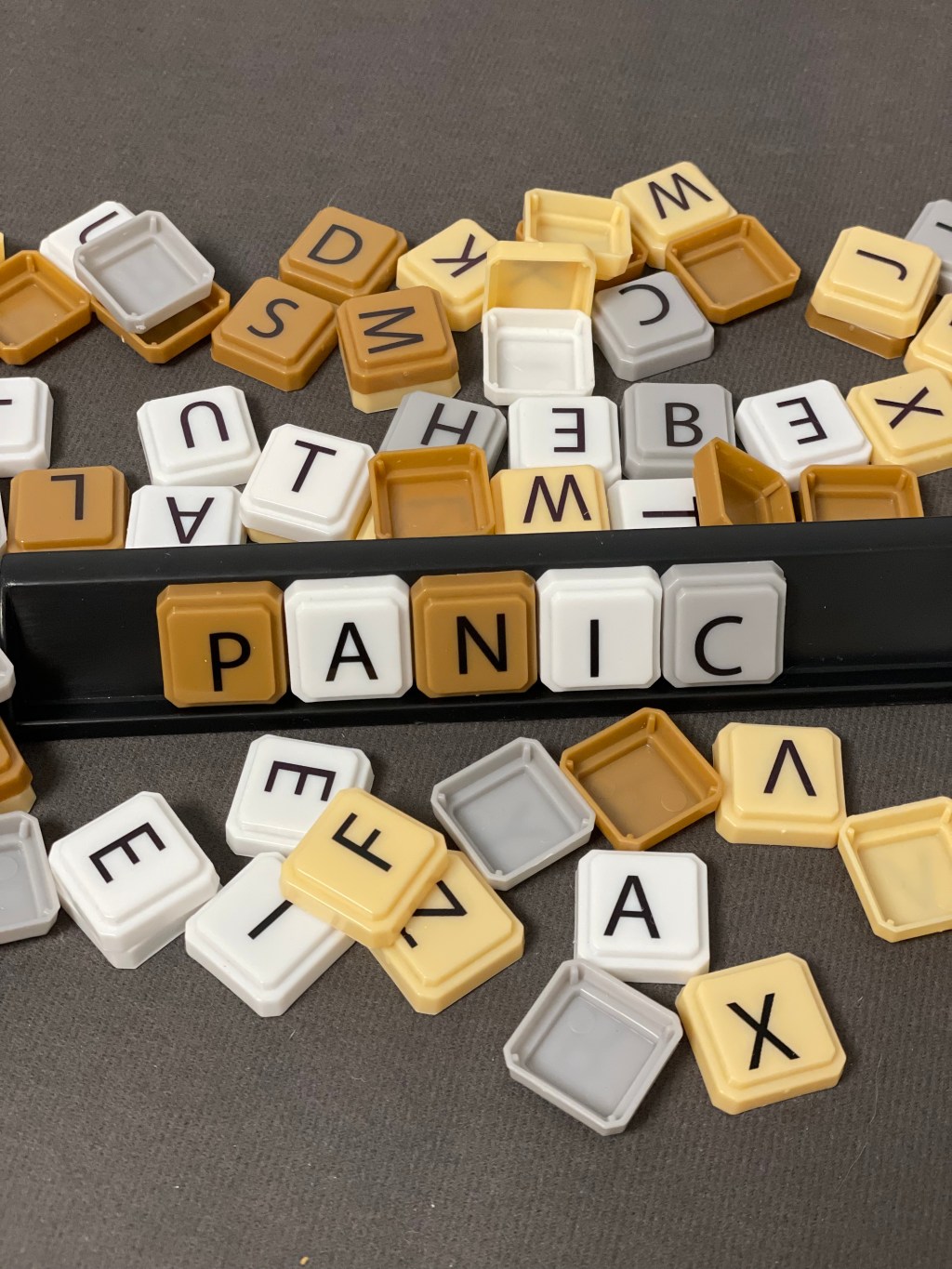

They don’t always come in order. In my experience, they rarely do. Sometimes they show up all at once. Sometimes not at all. And honestly, I think there should be two more: fear and avoidance. I’ve had my share of both.

It’s been a year and a half since I watched my mother die and that moment is seared in my memory. Since then, I’ve felt every emotion and welcomed the grief process—not always with open arms, but I chose to let it in.

And still, I resist anger.

I can be a very passive person. It takes a lot for me to get truly angry—the kind of anger that erupts, that demands to be heard. I imagine perfect anger as something almost beautiful: you scream, you cry, you throw things, you say what’s on your heart… and then it’s over. Truth has been expressed. You’ve emptied yourself.

But I worry that if I let myself go there, I won’t come back. That if I lose trust or hit my emotional limit, I’ll cross some point of no return.

My mother wasn’t an angry person. She had every reason to be, but she chose love. She voiced her frustrations. She lost her patience, sure—but I never saw her angry angry. My father, on the other hand, only knew anger. He was the angriest person I’ve ever known. And I often wondered what pain made him that way.

As a child, I made a quiet vow: I don’t want to be like that.

The upside is that I learned to control my anger.

The downside? I never learned how to express it.

But anger is human. Just like joy, like sorrow, like love.

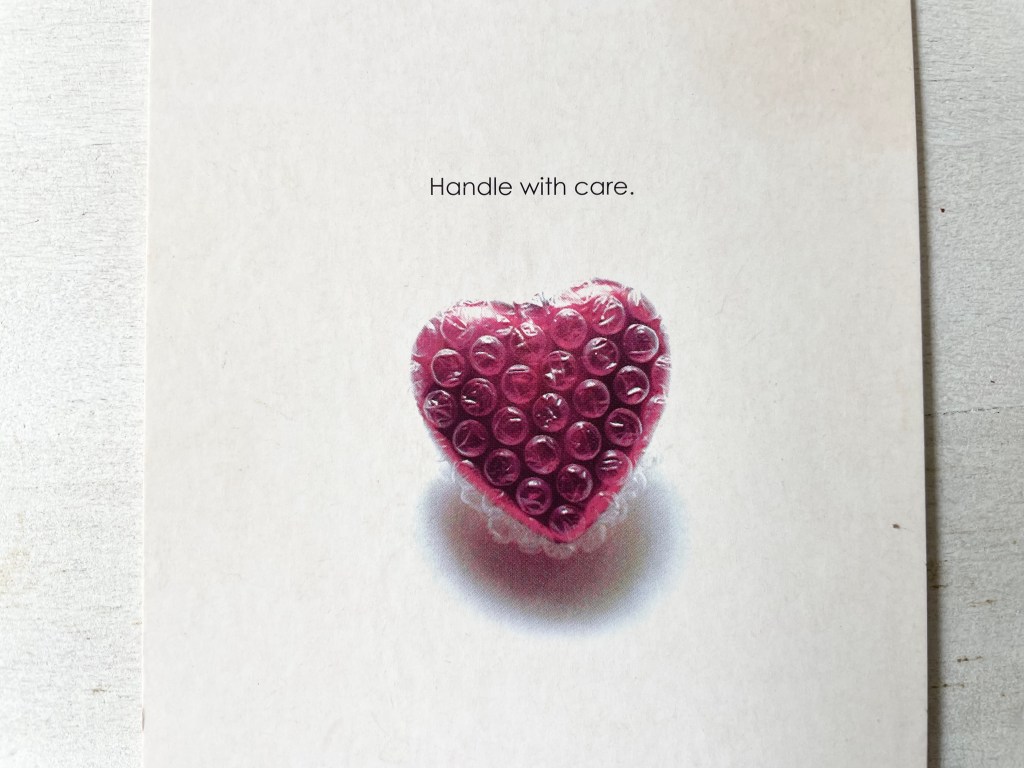

And maybe that’s the thing. Maybe all anger is, is heartbreak in disguise. Maybe I’m not angry. Maybe my heart is just broken. And maybe that’s what these stages of grief are really about: not just processing loss, but surviving heartbreak.

Because when you lose someone you love, your heart breaks. It cracks. It comes undone. You can’t control it, and it hurts. But if you let it—if you really let it—the light does start to shine through those cracks. You begin to feel joy again. You remember love.

I miss my mom.

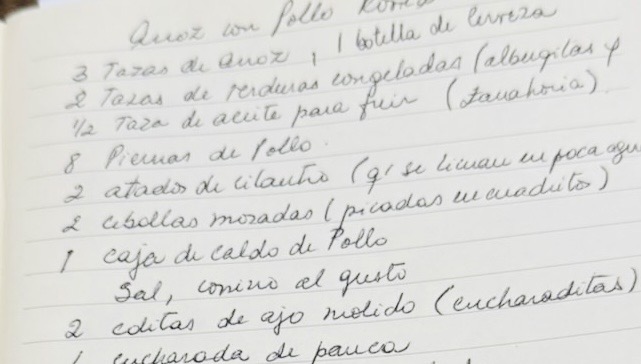

Our relationship was often backwards, but she was still my mother. She raised me. She made sacrifices for me. She taught me how to walk, how to love, how to be a person in this world. She held me when I was little, and somehow—no matter how old I got—she never really let go.

There was comfort in just knowing she was there.

In the sound of her voice.

In the smell of her home.

In the softness of her skin. Her beautiful hands.

In the unconditional love that let me be fully myself.

My heart is broken—for her, for me, for the way her life ended. For the love she gave but didn’t always receive. For the moments she never got to experience. For my son, who lost her too—and whose little heart cracked when she died.

Is that what we’ve been avoiding all along? Just… heartbreak?

Maybe fear and avoidance belong in the model of grief because we’re trying so hard not to feel the break. But what if we let it? What if we let our hearts break open just a little—enough for healing to find its way in?

As the great Pema Chödrön says,

“Begin with a broken heart—vulnerable and tender, shared with other people… Stay connected when you really want to withdraw. The vulnerable part is the human part. That’s the connection.”

Right now, all I feel is heartbreak.

I miss having a parent.

Even with all the role reversals, it was comforting to have her here.

Just knowing she existed.

I seek comfort now in small ways.

Some days, I’m too aware that I just want to be held.

Some days, I miss her so much that I look for her in the arms of the people I love.

That’s when I need their hugs the most—when my heart quietly asks for that embrace.

Maybe healing begins there.

With a broken heart.

And the choice to let it break… so that it can heal.